A History of Aromatherapy

Prehistoric Era

Aromatherapy shares a common early history with herbal medicine, of which it is a part. This is a history that extends thousands of years into the prehistoric past and chronicles the ancient relationship between human beings and plants. Archeological evidence from the Shanidar cave burials in Iraq has been interpreted as indicating that Neanderthal people in the area were burying their dead with flowers more than 50,000 years ago. This inference was made from the presence of flower pollen from several species, including yarrow, which was found with the skeletal remains, concentrated around the head. The amount of pollen found for some of the species suggested strongly that whole flowers had been placed in the burial but there has been lively debate in the field of archeology concerning whether or not the pollen might have been carried into the burial by rodents so this oldest evidence for the ritual use of plants remains speculative.

The archeological evidence for prehistoric ritual and medicinal use of plants by humans is fragmentary, especially prior to the Neolithic era (roughly 9000 to 3000 BCE). Most of the plants with the longest documented history of use are psychoactive in nature. In Texas and northeastern Mexico, for example, archeologists have documented a history of psychoactive plant use that extends back to 10,500 years ago. Psychoactive plants have a long history of use in the form of smoke for ritual and medicinal purposes and in this we find the earliest precursor of aromatherapy. In traditional cultures, plant smoke is still widely used in cleansing rituals and is believed to carry messages to the spirit world; this is why Native Americans burn sweet grass and sage, Hindus burn sandalwood, and native South Americans burn palo santo wood. The same belief underlies the burning of frankincense in Catholic churches which has continued into modern times.

Ancient Historic Era

The oldest written records that document the medicinal use of plants come from the ancient Sumerians who lived in Mesopotamia from 5500 BC.

They kept extensive written records on clay tablets that record the plants they used, what they used them for and their methods of preparation and the dosages. Aromatic medicine was highly regarded and pots have been found at Sumerian sites which are believed to have been used for primitive extraction of essential oils. In this method, clay pots were filled with plant material which was then covered in water; an absorbent material, probably wool, was stuffed into the opening and the pot was then heated. As the heated water turned into steam and rose towards the opening of the jar the essential oils were trapped in the wool, which could then be wrung out to produce a mixture of water and essential oil that would have been similar to today’s hydrosols. This product would most likely have contained at least a little lanolin from the wool as well.

They kept extensive written records on clay tablets that record the plants they used, what they used them for and their methods of preparation and the dosages. Aromatic medicine was highly regarded and pots have been found at Sumerian sites which are believed to have been used for primitive extraction of essential oils. In this method, clay pots were filled with plant material which was then covered in water; an absorbent material, probably wool, was stuffed into the opening and the pot was then heated. As the heated water turned into steam and rose towards the opening of the jar the essential oils were trapped in the wool, which could then be wrung out to produce a mixture of water and essential oil that would have been similar to today’s hydrosols. This product would most likely have contained at least a little lanolin from the wool as well.

Later the Babylonians, who lived in the same general area from about 3000 or 2000 to 600 BC, also left records detailing the use of fragrant plants and other medicinal herbs, including psychoactive plants such as datura, cannabis (controversial), claviceps, mandrake and poppy.

The Babylonians were followed in the Fertile Crescent by the Assyrians (628 to 626 BC) who preserved many of the old tablets from the Babylonians and also left their own accounts. What we know from this amazing collection is that disease at this time was largely considered to be the work of evil spirits or demons and the most common and respected way of driving out these demons was fumigation – smoking with fragrant herbs.

All essential oil producing plants can be placed on hot coals to produce fragrant smoke and some of the plants that they used this way, in addition to the hallucinogens and narcotics just mentioned, were calendula, chamomile, fennel, henbane, myrrh, saffron and turmeric.

There was a huge trade in aromatic plants in the ancient world, most often in the form of oils, gums and resins. The Babylonians imported frankincense from Africa and burned about 57,000 pounds of it a year. The Assyrians burned about 120,000 pounds of it a year in their annual feast of Baal.

There was a huge trade in aromatic plants in the ancient world, most often in the form of oils, gums and resins. The Babylonians imported frankincense from Africa and burned about 57,000 pounds of it a year. The Assyrians burned about 120,000 pounds of it a year in their annual feast of Baal.

The Egyptians were the ancient people who are probably most famous for their use of fragrant plants and I have seen reports that they utilized the same method of extracting essential oils that was employed by the Sumerians. They made extensive use of resins, dried plants, and infused oils and pomades. Among the fragrant plants used by the Egyptians for embalming, for religious rituals, and for healing were cedar, myrrh, and frankincense. In the 17th century, ancient Egyptian mummies were sometimes sold and actually distilled to be used as medicines themselves because even after thousands of years they were still impregnated with the residue of these aromatics.

The earliest historical accounts of the Egyptian use of aromatics date to about 4500 BCE – about 1000 years later than the Sumerians. However, the most famous historical document describing the use of aromatic medicine by the Egyptians is the Ebers Papyrus found near Thebes in 1872. The Ebers Papyrus was written during the reign of Khufu, around 2800 BCE, and describes the use of over 850 botanical remedies including myrrh, frankincense, myrtle, galbanum and many other aromatic herbs.

The use of aromatic plants has also been important in the ayurvedic tradition of India and a portion of the Rig Veda written around 4500 BC records the use of aromatic herbs.

Much later the Greeks and Romans made extensive use of aromatic plants, burning them as fumigants and using the infused oils both as perfumes and as medicines. As the Roman army moved over Europe and England, their uses of aromatic plants spread with them.

The Development of Distillation

It is the development of true distillation techniques that marks the historical roots of Aromatherapy, per se, and begins to set it apart from the rest of herbal medicine. The history of the development of distillation is unclear and often controversial, however. I have relied on Ernest Guenther’ seminal six volume set, The Essential Oils (originally published in 1948), for much of what is reported here about the history of distillation but some authors report different information on this topic. The best advice that I can give my students is to keep an open mind and simply be aware that things are not always cut and dried.

It is the development of true distillation techniques that marks the historical roots of Aromatherapy, per se, and begins to set it apart from the rest of herbal medicine. The history of the development of distillation is unclear and often controversial, however. I have relied on Ernest Guenther’ seminal six volume set, The Essential Oils (originally published in 1948), for much of what is reported here about the history of distillation but some authors report different information on this topic. The best advice that I can give my students is to keep an open mind and simply be aware that things are not always cut and dried.

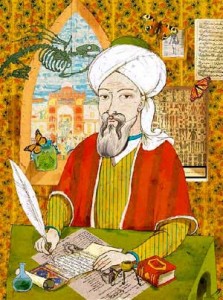

The discovery of the modern technique of steam distillation is usually credited to the Persian physician Aviecenna who lived between 980 and 1036 CE and succeeded in distilling rose essential oil. This must be suspect however as there is evidence suggesting that distillation techniques were being employed much earlier than Avicenna’s time. For example, the Greek historian Herodotus, who lived between 484 and 425 BCE, mentions oil of turpentine and gives partial information about its production.

A point that has often been overlooked by authors recounting the history of aromatherapy is that until the Middle Ages, distillation was carried out primarily for obtaining flower waters and the essential oils were not separated out as a specific product. In fact, as Guenther points out, when the process resulted in a precipitation of essential oils, as when rose oil crystallizes on the surface of rose water, the essential oil was likely regarded as an undesirable by-product.

It is unclear who developed the modern process of distilling essential oils. However, Arnald de Villanova, a physician who lived in Catalonia (Spain) between about 1235 and 1311 is said by Guenther to have made such praise of the remedial qualities of distilled waters that the process of distillation became a specialty of medieval and post-medieval European pharmacies. By the 13th century, essential oils were widely used in Europe by those who could afford them. They were used as fragrances by the nobility and it was a popular custom of the time to impregnate fine gloves with essential oils. Physicians of the era believed that being surrounded by pleasant odors would give protection against many diseases, especially the plague, as it was noted that many people who worked with essential oils, such as perfumery workers and glove makers, did not succumb to the illness.

A hundred years later the European alchemists of the 15th century, including Paracelsus, continued to perfect the process of distillation and added many new essential oils, which began to be more widely used as perfumes. By the 16th century, the perfume industry was one of the most important industries in Europe.

A hundred years later the European alchemists of the 15th century, including Paracelsus, continued to perfect the process of distillation and added many new essential oils, which began to be more widely used as perfumes. By the 16th century, the perfume industry was one of the most important industries in Europe.

By the 16th Century, production of essential oils was widespread and many manor houses in England and Europe had still rooms devoted to the production of flower waters and essential oils for both household and medicinal uses.

From the 16th to the early 19th centuries herbal medicine in general, and aromatic medicine specifically, continued to expand and, of course herbal medicines, including essential oils, were the only medicines we had until the 19th century. As synthetic drugs became the gold standard for western medicine’s treatment of illness and the pharmaceutical industry became the powerful force that it is today, herbal medicines of all types fell by the wayside in most developed countries (China is a notable exception). However, according to the World Health Organization, the majority of the world’s population still largely depends on traditional medicines based on medicinal and aromatic plants and for many people in developing countries herbal medicines are still the only medicines that are available. In many cases, herbs are used today in the same ways that they were hundreds and even thousands of years ago and in some instances these ancient medicines have applications in the treatment of a diverse range of illnesses such as cancer, infections, kidney stones and many others that are unmatched by pharmaceutical drugs.

Copyright © 2011 Joie Power, Ph.D. / The Aromatherapy School | All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.